[1.0] My Data Union’s purpose

Every internet click, search, and swipe you make is knowledge. This knowledge is rightfully yours, and yet others capture it, use it, and profit from it as if it were their own. You need help to protect your property and demand a fair share of the wealth it creates. My Data Union can show you how to do it the right way.

There is a large market that already trades on a steady supply of people’s data. Although consumers may not realize it, their information powers tens of billions of “real-time bids” for ads on their devices every day.[1] It provides AI-tool developers the food they need to feed their advanced models. Banks, insurance providers, and investment funds analyze it be the first to know how to capitalize on emerging trends. Despite producing valuable profits for many, the creators of this data are systematically stripped of ownership and robbed of choice. The market was not built for the consumer. Instead, they are forced to participate and left vulnerable to hordes of dubious middlemen. People need transparency, fair compensation, and representation to make their property work for them and not the other way around.

The status quo of the market is not sustainable and must be restructured. It rewards opacity, not fairness, and data trades inefficiently. As the rightful owners with highest knowledge base of their own data, people need the ability to mutually benefit in consensual transactions. Participation requires knowledge and understanding of what information is already taken from them, how it is taken, and what it is worth. After that, people need collective representation and aligned incentives to ensure their choice is respected. These services do not exist today, until now.

My Data Union was created to fill the void. It pools its members’ digital property and best interests together to serve as their representative in a market that has long ignored them. Members use My Data Union’s resources to learn about the value of their data, to safely gather their data, and to find qualified buyers for their data if they choose to sell. My Data Union negotiates terms with other companies on its members’ behalf and provides them with digestible summaries. Through the services, members can take back their agency and restore their lost wealth.

[2.0] Changing the status quo

Today’s digital marketplace lacks representation from its most important stakeholder: the consumer. A healthy marketplace depends on competitive tension from ALL participants. My Data Union was created to correct this imbalance by providing a platform that allows members to access, understand, and participate in the data economy on equal footing.

Most people underestimate how much information is collected about them and how valuable it is. Limited access, awareness, and resources make it nearly impossible for individuals to understand or capitalize on their own data. Meanwhile, companies that buy, sell, and handle consumer data have no financial incentive to help. Relying on government regulation and intervention is equally unrealistic. The next sections detail how My Data Union interacts with the industry’s participants to secure fair compensation and treatment for its members.

[2.1] Aggregating data

The digital marketplace rewards those who collect extensive data about vast numbers of consumers. It is virtually impossible for individuals to find willing buyers. Members use My Data Union to provide transparent data aggregation methods to safely anonymize their information, combine it with other members’ data, and solicit qualified buyers. For its effort, My Data Union earns a commission after it negotiates and sells members’ data for the best price, to qualified buyers, perfectly aligning its financial incentives with members.

The companies that currently aggregate people’s data disguise their motives. “Free” or discounted services manufacture the illusion of consent while quietly mining their users. The usual suspects include social media and news platforms, travel services, mobile app developers, and search providers. Other participants reward users with loyalty points and discounts, such as credit card providers, grocery stores, coffee shops, and brands. All their financial incentives are clear: gather as much information as possible, monetize it in every conceivable way, and give as little as possible to the consumer who created the data. Their business models contradict the financial incentives of its users.

Most aggregators monetize their user information in two main ways:

- Price optimization – using data to set prices and maximize profits

- Advertising – selling targeted ad space.

A third, far more opaque practice has emerged: selling user profiles to third parties.

My Data Union takes the opposite approach. There is no confusion about the relationship; members offer data voluntarily, see what it is worth, and earn money alongside My Data Union when it is sold. This alignment of interests builds trust to grow members’ wealth.

My Data Union’s approach allows members to outcompete other data aggregators and maximize their digital property’s earning potential. Instead of finding creative ways to repossess their property, My Data Union’s business model rewards consumers who gather and bring their valuable information to the marketplace. Like other precious resources, buyers pay a premium for what they cannot get elsewhere. No other market participants can provide the same level of knowledge consumers possess about their own activities on their own devices and services. My Data Union provides its members with more than aggregation services; its presence in the market will lure buyers away from sketchy middlemen to consumers themselves.

Not only does My Data Union’s platform provide the market with the highest quality consumer data, but it also gives buyers a single point of access for consensual, comprehensive data. Buyers spend a lot of time and money finding data aggregators that legally offer both the scale and diversity of data they need. For example, transaction data comes from different payment networks, digital wallets, and credit card scanners. Demographic and social media data are provided by thousands of different companies. Geolocation data comes from a patchwork of substandard vendors. Many of the industries’ aggregators operate unethically, and even illegally, amplifying theft and fraud on consumers.[2],[3],[4] Almost none of them provide data that the consumer cannot safely gather themselves. My Data Union gives its members the tools to consensually compete. The result: members are rewarded for making the marketplace more efficient.

[2.2] Defining consent and negotiating for fair treatment

Consumers conduct business directly with the companies offering them convenience. Those companies exploit individuals’ lack the resources, expertise, and leverage to negotiate. The terms are so lobsided that people even cannot see the data they give away for free, much less understand what it is worth. As a result, their best interests are routinely disregarded since they cannot do anything other than accept the terms they are presented. They need a trusted intermediary to intervene on their behalf to limit what data is collected, understand how it is used, and how it is valued.

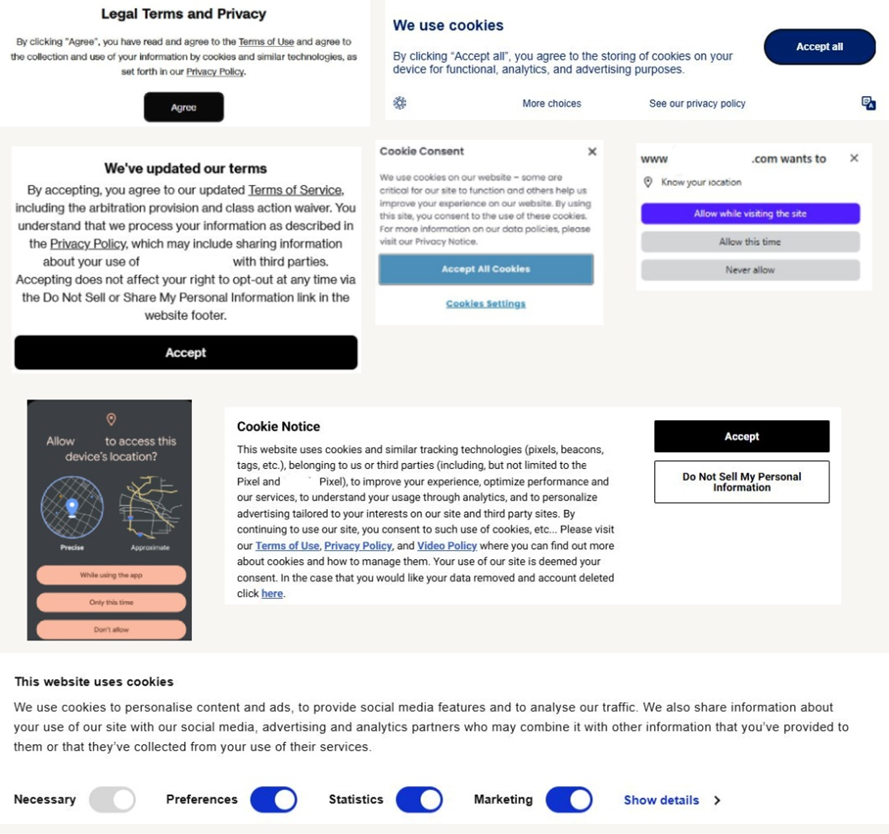

The status quo is so broken for consumers that it is not even clear if or when they provide consent to a transaction. The exhibit above depicts the industry’s preferred method for manufacturing approval to drill consumers for their data. Consumers are expected to interpret and determine onerous terms-of-service agreements on the spot when they buy a service or visit a website. They are forced to interact with annoying, confusing pop-ups and cookie notifications that declare open season if it is accidentally clicked or swiped incorrectly. This is not a serious way to conduct business for sensitive, valuable property.

Companies do business like this because consumers are not organized; there is no reasonable solution for even the most well-intentioned company. Fair treatment requires organized consumers who are represented when the terms are being drafted. Organized consumers require oversight to know what data is supplied and price transparency to know what it is worth. My Data Union positions itself between its members and data collectors to serve as their collective representative so it can negotiate on behalf of a unified group of users to set terms, detail and price the consumer data being exchanged, and generate negotiating leverage for its members. After this process takes place, members are equipped to decide how they would like to proceed. Regardless of what they choose, My Data Union serves to make sure their decision is respected by all.

[2.3] Finding and negotiating opportunities

Data buyers come from many industries and the most common are brands, marketing agencies, financial institutions, investment firms, artificial-intelligence developers, and political groups. They pay substantial sums of money for access to quality consumer datasets, ranging between $5,000 and $1,000,000 per subscription per year! Organized consumers offering their data in large, anonymous pools can attract these wealthy buyers. My Data Union steps up for members by finding qualified buyers and negotiating for the best prices.

Brands and their marketing partners purchase consumer data to understand purchasing behavior and optimize product campaigns. They analyze browsing, transaction, and engagement data to refine product design, pricing, and promotion strategies.[5],[6] Measuring and forecasting consumer trends is big business that allows companies to quickly identify and capitalize on emerging trends before competitors.[7] In addition to providing basic demographic information that is already widely distributed, organized consumers can supply buyers by offering timelier and more comprehensive datasets that other participants cannot or are not incentivized to offer.[8] A clothing brand may not want to pay for ad space targeting consumers who recently purchased their products. An emerging ride-sharing company could want to study data about established companies’ most frequent routes to offer consumers a better price and service.

Banks, credit bureaus, insurers, and lenders are among the most voracious buyers of consumer data. They buy seemingly obscure data points, such as rental payments, social network information, and surveys, to build sophisticated risk models.[9] Their goal is to discover unique data combinations that minimize loss exposure and maximize profitability. Buyers source some of their data from popular Buy-Now, Pay-Later and other companies who access consumers’ sensitive financial data.[10],[11],[12] As discussed later, the risk consumers face from theft and fraud increases for each new company with access to their sensitive information. Consumers need control over what is shared and to provide a single source of truth, thereby eliminating the need for hundreds of middlemen who do not handle their information with care.

Real estate management companies rely on geolocation, demographic, transaction, and social media data to identify migration patterns, consumer preferences, and spending trends. This intelligence helps them select optimal sites for development or acquisition and target the right commercial tenants. Certain data prices are extremely volatile and require specialized knowledge to know its worth at a particular time. COVID-19 disruptions highlighted the value of timely consumer location data and created a windfall opportunity. Unfortunately, the benefit was taken by data brokers, and the people who were unwittingly tracked suffered. It is vital for consumers to take ownership because not all their location data is created equally. A consumer may not care others sell knowledge about what stores they visited last week, but they probably do not want to sell a heat map detailing their recent visit to an abortion clinic.[13] Clearly, some information is not meant to be shared and it is vital for consumers to organize with company who provide the necessary autonomy and transparency so consumers can make informed decisions for themselves.

Investment firms purchase large volumes of consumer data, including credit card transaction logs, store receipts, and foot-traffic data to anticipate corporate earnings and changes in consumer trends. They measure, in almost real-time, which companies are getting bigger or smaller, spending differences between consumers with different incomes, and average transaction values per store.[14] Some even analyze consumer sentiment mined from investing tools, online forums, and comment sections to predict their behaviors.[15],[16] Consumers need a transparent and easy way to visualize what information could be useful as well as a trusted, aligned source to help them competitively price it.

AI toolmakers represent a fast-growing group of data buyers. They highly value the quantity, diversity, and authenticity of consumer datasets because it impacts the performance and accuracy of their AI-models. While some developers may be extracting data without consent from users and websites, many more will spend a lot of money to legitimately source high-quality datasets.[17],[18] Organized consumers signal to these new buyers that they are ready and able to conduct business appropriately.

Political campaigns and advocacy groups, particularly in the United Sates, use consumer data to sharpen their messaging and target voters with precision. They purchase survey results, migration data, browsing histories, and demographic profiles to identify persuadable audiences and allocate advertising budgets to reach the right people, with the right message, at the right time. Consumers need transparency to learn who wants their information, what their purpose is, and how much it is worth so consumers can decide for themselves what, if any, information to offer.

Despite their sophistication, data buyers face persistent inefficiencies driven by unreliable sources, fragmented markets, and inconsistent data quality. Consumers can address these issues at their foundation by uniting within a transparent marketplace. My Data Union’s platform provides verified, consensual, and comprehensive datasets that reduce friction for buyers while delivering agency and fair compensation to its members. The model properly aligns financial incentives across the ecosystem and promotes a more efficient, ethical digital economy.

[2.4] Integrating with ad-exchanges

Sophisticated markets already trade with consumer data. Organized consumers can plug directly into the market and monetize their knowledge. Like stock exchanges, ad-exchanges are where buyers and sellers meet using advanced algorithms to trade at high frequency. Tens of billions of automated auctions are conducted every day to determine which ads appear and at what price.[19] Every party involved relies on one crucial element: knowledge about the consumer. Small details, such as knowing whether an anonymous person is at home or recently purchased pet food, can prove extremely valuable.

Consumer data is the foundation of this system. Information is continuously distributed among buyers, sellers, and intermediaries to optimize targeting and pricing. Yet, as discussed later, this knowledge is distributed haphazardly and handled irresponsibly. The companies involved are motivated to use the data, not to protect it. It is not their property, after all. Currently, no adequate safeguards or market mechanisms exist to address this imbalance.

My Data Union introduces a transparent approach for members to find, price, and protect their property. Through its platform and membership base, it serves as a trusted intermediary that enables companies to query anonymous, aggregated datasets rather than sharing sensitive personal information with dubious sources. Members maintain full control over what data about themselves is offered, and when it is, they receive fair compensation for participating. Replacing opaque and inefficient systems with consent-based exchanges for consumer information redefines how consumers can safely prosper and participate.

[2.5] Consolidating data suppliers

My Data Union and its members remove the need for most data brokers in the marketplace by offering data directly to buyers. Data brokers, who are the shadiest and least accountable actors in the digital economy, quietly insert themselves in many ways to exploit the consumer’s property. Instead of conducting business with consumers, data brokers go around them to take their property from data aggregators, other data brokers, and even distressed or bankrupt companies. Their primary function is to combine consumer data from multiple sources – often linked through a consumer’s email address, physical address, phone number, or other identifiers – to construct comprehensive behavioral and demographic records. Data brokers’ incentives and principles run counter to people’s best interests; they want to take everything from the consumer and pay them nothing.

Data brokers do not want people to know about their heists happening every day. Common data collection methods include mining public records, scraping online profiles, and conducting surveys. However, as explored later in the section “Hidden costs paid by consumers,” brokers employ far more invasive and under-disclosed tactics to acquire sensitive information. Nearly all of this activity occurs without the consumer’s knowledge or consent. They would prefer to do their business outside of view to conceal their methods and profits from consumers’ digital property. My Data Union intends to publish proprietary research and engage in market activism to shine a light on their activity.

Compared with other participants in the data economy, data brokers go through shorter and more volatile boom-and-bust cycles, frequently leading to ownership changes. This instability is not incidental; it is a feature of a business model designed to ensure that data never truly disappears. Minor changes to legislation governing collection tactics, public scandals, or mobile security updates can trigger financial distress, resulting in bankruptcy proceedings or asset sales. For now, data buyers tolerate the friction because there is no viable alternative.

No one understands consumers better than the consumer themselves. Those who organize can collect everything data brokers gather, and more. They are the natural supplier for the most accurate, timely, and comprehensive consumer data on the market. Organizing with My Data Union and leveraging its collective representation enables consumers to capture the very value most data brokers exploit for themselves and remove them from the market forever.

[2.6] Monitoring and enforcing compliance

My Data Union’s member-first structure solves a problem that challenges most tech companies competing globally. Every jurisdiction defines its own rules governing how consumers’ digital property is collected, processed, and monetized. As previously mentioned, data collectors’ business models run counter to its users’ best interests, thus making compliance a never-ending battle. Below are examples of legislation that molded My Data Union’s design. At the core of all these frameworks lies a shared goal: defining what constitutes consent and determining what information rightfully belongs to the consumer.

In the United States, data brokers must register in certain states to establish a baseline level of oversight. Those operating in California are held to a higher standard due to the ‘California Consumer Privacy Act’ and “California Delete Act,” which requires companies to process deletion requests and submit to independent audits. Other states, such as Texas, Oregon, and Vermont, enacted similar laws. Entities in the European Union must comply with the far stricter “General Data Protection Regulation,” which governs consent, collection, analysis, and deleting protocols for consumer data with greater rigor.

In the United Sates, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is charged with educating and protecting consumers while promoting fair competition. In theory, the framework empowers consumers to compare prices between similar goods and understand the terms of services they accept. Unfortunately, its rules are antiquated, and the agency does not bring criminal cases. Most violators view penalties as a cost of doing business rather than a meaningful deterrent. Consumers rarely learn when violations occur, and when compensation is awarded, it often arrives years later and in negligible amounts.

Significant gaps in compliance challenge the enforcement efforts of legislators and regulators. Many dubious data brokers register their companies abroad in jurisdictions that offer little or no transparency, accountability, or enforcement for individuals abroad. For example, Israel, Singapore, and China are common havens for illicit operators collecting North American, South American, and European consumers’ data. Others evade detection entirely by creating layers of shell entities to avoid registration and oversight outright.

Regulation alone does not protect consumers. They need a transparent solution from an industry participant with aligned financial incentives to negotiate for proper treatment. Compliance and alignment are features, not burdens for My Data Union. By putting members’ digital property rights first, My Data Union can operate within and across jurisdictions with full transparency. Its platform enables lawful, ethical data transactions worldwide, supplying buyers with the scale and reliability the industry has long lacked, while compensating members fairly for their participation. This creates a healthy system that rewards compliance and makes it far easier to identify and remove bad actors.

The true price of inaction is paid discreetly and continuously by the very people who supply the data powering the digital marketplace. The forthcoming section, “Hidden costs paid by consumers,” explores the extraordinary lengths to which data brokers go to exploit people’s digital property.

[3.0] Hidden costs paid by consumers

Consumers are routinely tricked to pay more for their products and services using a currency they neither understand nor can measure – their data. Even the most diligent person, with unlimited time and resources, could not possibly account for the full value of the information being collected about them at any given moment. When multiplied across every digital service and every year of activity, this imbalance becomes systemic disenfranchisement of all consumers.

People pay the hidden costs of a misaligned and inefficient market with the value of their digital property and lost privacy. The following sections discuss several examples along with how My Data Union helps members reduce the costs and claim lost income.

[3.1] Price deception

Businesses know consumer data is valuable but lack the obligation and incentive to disclose it in clear terms. Consumers are encouraged to trade precious information for convenience, unaware of how much they truly give away. My Data Union’s tools help members understand how their data is extracted and what it is worth so members can compare prices among products on like terms.

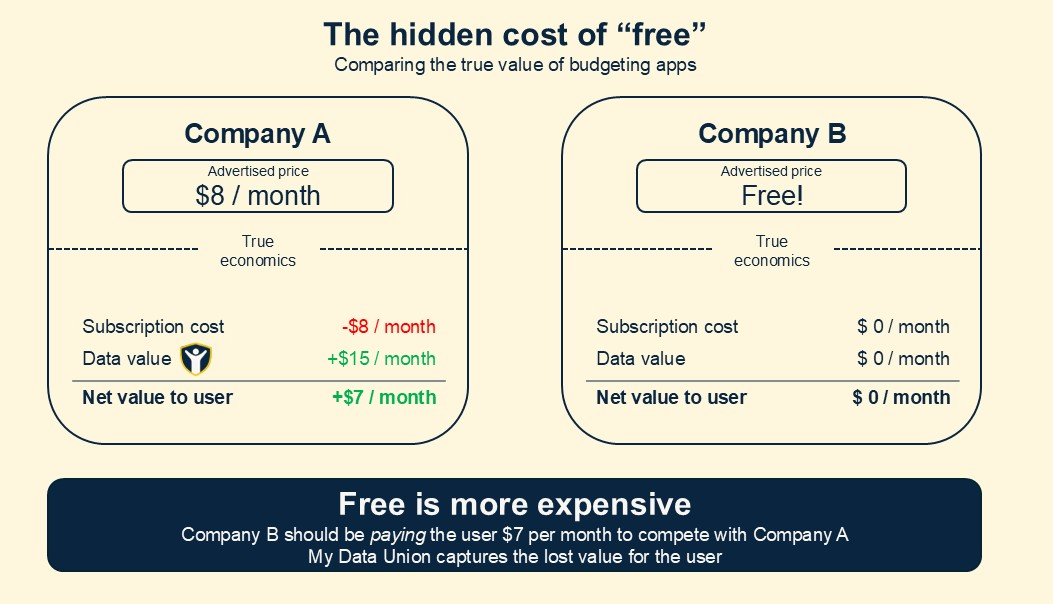

“Free” services come with hidden costs that often make it the most expensive option. For example, many consumers rely on “free” apps to help them budget. The services access their bank accounts and record their transactions. Although the apps help their users by collecting, classifying, and managing users’ financial life, they also take and sell valuable knowledge about them.

Consider the example below. Company A and B offer identical services but advertise different prices. Company A charges $8 per month and Company B offers its service for free. At face value, Company B seems like it offers the best deal. In reality, this is not the case, and My Data Union provides visibility into the true cost of these services.

A member of My Data Union can quickly learn that Company B captures and sells the user’s demographic, financial, and behavioral data to data brokers at a value of $15 per month. Company B takes away people’s agency. Company A, on the other hand, does not capture or sell user data. If the member wants to sell all of the data produced by Company A for $15 per month, My Data Union can do it on their behalf, resulting in a net benefit to the user of $7 per month. When considering these factors, Company A provides better value to its users. Company B should be paying its users $7 per month to make its offer comparable to Company A’s.

One of My Data Union’s founding principles is the understanding that members are the rightful owners of their data and maintain autonomy over it. Company A alongside My Data Union provides members with more choice and profits than Company B. For example, a member who uses Company A can choose to sell all their data for $15, some for $5, or none. They can also change their mind at any point. Company B’s proposition is all-or-nothing, and their stance does not give this type of flexibility to its users.

When equipped with the right tools and transparency, consumers can make rational choices for themselves. If a member prefers Company A, My Data Union can collect and monetize the data for them, or they can keep their data private. If the member prefers Company B, My Data Union can negotiate with Company B to secure fair compensation for their property, ensure their sensitive information is protected, and the terms of agreement are honored. Members choose for themselves which option works best, and My Data Union executes.

[3.2] Reducing transaction costs

People are conditioned to believe the price they pay for digital products and services is the dollar value shown at checkout, but modern prices are paid with dollars AND data. The latter is a deferred payment charged every single time consumers use their digital products and services to generate data. This presents a dilemma: what is each deferred payment of data worth, and who assigns the value? Companies know consumers cannot answer that question, so they take advantage of information asymmetry by forcing consumers to pay high transaction costs when they interact with digital products and services. These are telltale signs of a very inefficient market. Through collective representation, members can profit by providing efficiency and avoid falling victim to predatory exchanges.

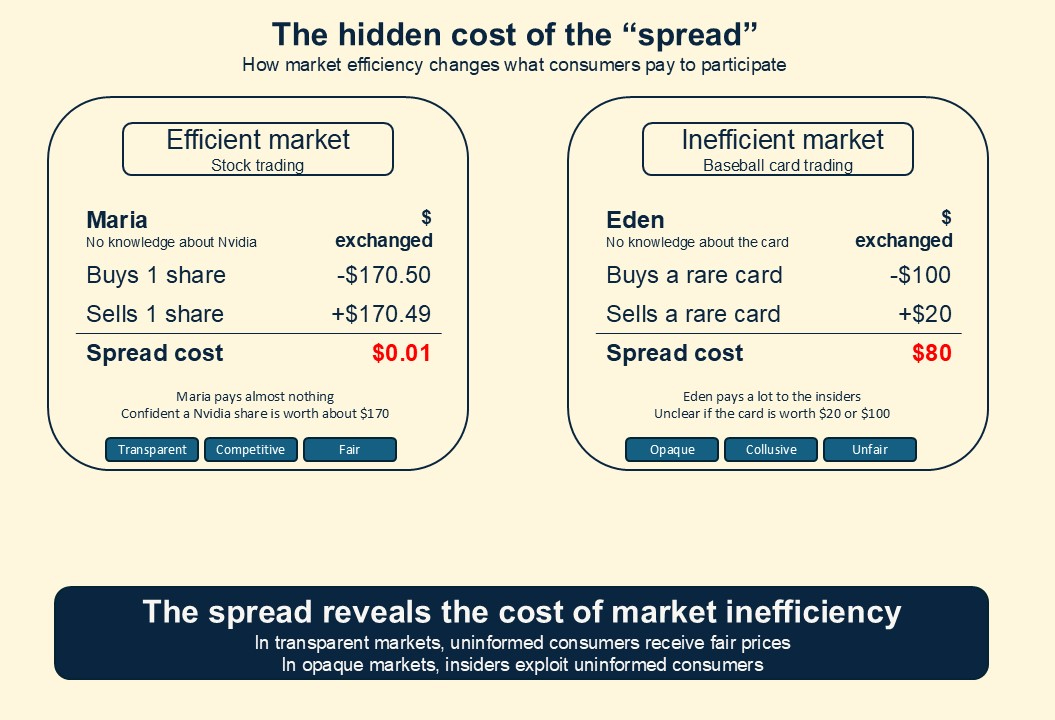

A hidden transaction cost consumers pay for not knowing the assigned value of their data is called the “spread.” The spread is the difference between 1) the highest price at which someone is willing to buy and 2) the lowest price at which someone is willing to sell something. The wider the spread, the greater the transaction cost. Information asymmetry between participants creates wide spreads for inefficient markets, such as the market for consumer data. Consider the following illustration of two consumers, Maria and Eden, trading in the stock and baseball card markets.

Inefficient markets, like those for collectibles, are opaque and reward insiders who abuse information gaps. Eden, for example, wants to buy a rare baseball card for her nephew. With little experience and few options, she finds a single dealer who offers her a card for $100, and who insists it is rare and worth more. Eden has no way to verify the claims. Pressed for time, she buys it only to discover later she purchased the same card as someone else…who paid $60 for the card. Eden returns to the baseball card trader and demands they buy it back so she can buy another gift. The baseball card trader knows Eden does not have the ability or willingness to sell the card to someone else tonight and bids $20 for the card. Eden reluctantly accepts, knowing she has no other viable option.

The consumer data market resembles Eden’s experience. It is very inefficient because individual consumers have no access to transparent pricing, negotiation power, or diverse buyers for their data. Organized consumers push the market to efficiency and directly benefit from their efforts.

Very efficient markets, such as public stock exchanges, trade with narrow spreads and minimal costs for all participants. The primary factors that contribute to market efficiency include:

- Equal access to publicly shared information and resources;

- A diverse pool of participants trading for different reasons;

- Transparent terms and oversight.

The stock market rewards strategy and competition where participants must offer to buy and sell at fair or risk being ignored. In this market, if Maria wants to buy one share of Nvidia, she can see what others have recently paid and knows there are many sellers with different motivations. Maria pays $170.50 for a share, a price comparable to thousands of offers she received. Because the market is transparent, she can confidentially ignore predatory offers for $300 per share. Shortly after buying the stock, Maria needs to sell it immediately. She receives thousands of similar bids for $170.49. She accepts a competitive bid and disregards opportunists bidding $120 per share. Transparent pricing and competition protect her from exploitation.

Another way of framing the cost incurred by the spread is the consumer’s confidence that they received a fair offer. In the example above, what is Eden’s card worth? Is it the $100 she paid, $60 someone else paid, or $20 she received upon selling? The only information she can infer is that it is worth somewhere between $20 and $100 – a very wide range. If the card’s fair value is $60, then Eden overpaid by $40 ($100 – $60), and was undercompensated by $40 when she sold ($60 – $20). Eden indirectly pays a lot due to her lack of knowledge. In contrast, Maria is quite confident Nvidia shares are worth about $170.50 and paid very little due to her lack of knowledge.

My Data Union improves data market inefficiency by introducing tools for price discovery, collective negotiation, and clear data valuation. It turns an opaque marketplace into a fair and competitive one. Organized consumers signal to participants that they are informed and require fair terms for their property while My Data Union provides the structure, qualified buyers, and transparency to make it possible. Members choose for themselves what comes next knowing My Data Union is there to support their decision.

[3.3] Reducing property theft and fraud

My Data Union’s principles plainly state its members are the rightful owners of their digital property and aligned its financial incentives with its members. Privacy and protection create scarcity which, in turn, increases the price of consumer data. The incentive motivates My Data Union to provide members with the best tools and know-how to aggressively defend their property against thieves, reducing their risk of fraud in the process.

Data brokers, and the aggregators who supply them, systematically separate people from their property. Consider one type of digital property, geolocation data:

- Diego, a consumer, downloads a popular mobile app.

- The app requires or repeatedly asks for his location, network, and Bluetooth permissions. Diego grants permission.

- The app then records all available location data, even when Diego is not actively using it.

- Unbeknownst to Diego, the developer is compensated by data brokers to transmit his geolocation, network, and device data.

- Without Diego’s explicit consent, the developer removes Diego’s name from the data he created and licenses it to the data brokers.

- In effect, Diego’s digital property is now entirely controlled and monetized by the app developer and its network of brokers.

This process repeats across hundreds or thousands of mobile apps and websites. With enough cross-referenced data, data brokers can easily reidentify Diego, tracking everywhere he visits, when he visits, what he does while visiting, with whom he visits, and how long he visited to create a comprehensive and marketable profile. People need collective representation to define how consent is given, what information can be gathered, and how much they expect to be paid to participate.

Beyond economics, these practices impose serious privacy and safety costs on consumers. The scope and sophistication of data harvesting are staggering, hidden, and always evolving. They need help to stay informed. As previously cited, several major data brokers were reprimanded for selling geolocation data of people visiting abortion clinics.[20] Scandals like this revealed a common tactic – data brokers pay developers to embed their code directly into mobile apps, enabling them to harvest consumer data while evading consent requirements.[21] Disturbingly, these integrations often appear where users least expect them, such as mobile games, travel apps, dating platforms, shopping platforms and assistants, weather apps, and even prayer apps.[22],[23]

Vigilant consumers have no reliable way to detect or prevent this activity alone. Because personal data passes through so many intermediaries, none of whom are financially motivated to maintain strong security, breaches are inevitable and devastating.[24] Email addresses, physical addresses, Social Security numbers, real names, social media profiles, and phone numbers are among the most valuable targets. Once exposed to the black market, the data enables identity and financial fraud, leaving its victims struggling to recover. Meanwhile, the companies directly or indirectly responsible often provide little assistance or accountability in the fallout. This raises an uncomfortable but necessary question: How and why do so many companies have my information?

Every entity that holds a consumer’s data presents a new access point for theft and fraud to occur. Imagine a goalie on the soccer pitch. Thwarting attackers from scoring on a single goal with proper training and equipment is a manageable task. Trying to stop attackers from scoring on one of a hundred goals is hopeless. My Data Union’s platform provides the single source of the highest quality, most reliable, and consensually supplied data from its members, reducing exposure to the middlemen who do not handle it with care.

When consumers lose control of their digital property, the consequences reach far beyond privacy concerns. The same systems that profit from weak data protections also facilitate widespread fraud. Its costs are hidden, indirect, and ultimately borne by those least able to prevent them. My Data Union restores balance by giving consumers collective power to safeguard their data, limit its use, and reclaim the value that would otherwise be lost to exploitation.

[3.4] Cost of fraud

Like inflation, fraud is a pervasive but difficult-to-measure cost that is paid by consumers, eroding their wealth over time. Although the public rarely sees its full impact, fraud imposes real and lasting financial consequences across the economy. New solutions are needed so the consumer is not stuck paying for industry’s negligence.

Consider a simple example of payment fraud and how it affects the price of everyday goods and services:

- A thief illicitly acquires a consumer’s, Jackson’s, credit card information.

- The thief uses Jackson’s card to purchase a new phone from Company A.

- Jackson, or his credit card issuer, detects the fraudulent transaction.

- The credit card issuer reimburses Jackson and gives him a new card.

From Jackson’s perspective, the issue seems resolved in his favor. But what he doesn’t see is the ripple effect:

- The credit card company normally charges merchants a 4% transaction fee on every sale.

- After a rise in fraud-related losses, the company increases its fee to 5% to cover costs.

- All merchants raise their prices to offset the higher fees.

Jackson, and every other consumer, pays for fraud indirectly through higher prices at the cash register.

This example highlights a deeper structural problem: consumers lack representation in the systems that determine the costs of fraud, security, and data handling. When one group is absent from negotiations, the remaining participants are free to collude against them. Nowhere is this imbalance more pronounced than in markets that trade, process, and profit from consumers’ digital property.

[3.5] Malicious extraction methods

My Data Union believes sharing exists on a spectrum; most people want to share some information, not all or none. People should be given enough information so they can decide for themselves how much to share. Unfortunately, today’s consent systems fail to reflect this nuance. Once a consumer grants even minimal permission, they are often exposed to a frenzy of unchecked data harvesting. My Data Union provides its members with tools and knowledge to detect and mitigate unfair collection practices.

The following section outlines common data-mining tactics used by data brokers who embed their code into popular mobile apps. With thousands of apps and internet-of-things devices funneling user data to them, brokers build intricate, precise surveillance networks that monetize consumers’ digital property without their awareness. Individually, none of these methods are inherently malicious. However, when combined and deployed without explicit, informed consent, they constitute what My Data Union considers identity fraud. Organized consumers benefit from My Data Union’s know-how so they can stop unwanted incursions.

[3.5.1] WiFi and network triangulation

Applications commonly request permission to view and access nearby WiFi networks. Data brokers, and their app developer partners, exploit this to access a user’s location with surprising precision. Often within 10 meters.[25] The process typically follows the following formula:

- Nari, a consumer, downloads an app that quietly transmits her data to brokers.

- The app continuously scans and logs all nearby networks visible to her device.

- While Nari’s device is in public…

- Data brokers reference vast directories of known networks and their geocoordinates.

- By analyzing the device’s signal strength between Nari’s device and those networks, data brokers can triangulate her device’s location even without connecting to the network.

- While Nari’s device is in private…

- Frequent signals during the day or night reveal which networks are likely her home and work.

- By scanning for other devices on the same network, brokers infer with whom she associates with and what devices she uses

[3.5.2] Bluetooth low-energy triangulation

Applications requesting Bluetooth permissions can give data brokers even more precise and stealthy access to a user’s movements. Small devices known as “Bluetooth beacons” transmit low-energy signals detectable within one meter, often without the user’s knowledge.[26] Left unchecked, scores of companies can carefully monitor an unsuspecting passerby.

Publicly, these beacons are placed in stores, airports, venues, and other high-traffic locations. Privately, consumers place them on their keys, pets, devices, and family members so consumers can locate them easier. Certain mobile apps quietly log beacon transmissions, even while offline. By matching signal data with their beacon directory, brokers and their app partners can map detailed migration patterns of consumers. Each beacon can operate for years on a single battery, enabling long-term surveillance with minimal cost and interruption.

[3.5.3] Bankruptcies and divestitures

The data broker industry is volatile, with companies frequently merging, selling assets, or collapsing altogether. Yet the consumer data they collect rarely disappears. Instead, it changes hands repeatedly, producing a boomerang effect that makes compliance and accountability nearly impossible.[27] Consumers need a company aligned with the financial value of their data so to make sure stolen data stays out of the market.

As firms approach financial distress, they often treat consumer data as property they can monetize aggressively. Once bankruptcy proceedings begin, the databases containing names, addresses, phone numbers, emails, and geocoordinates are discreetly sold to the highest bidder. Legal liabilities are left behind with the defunct entity, while sensitive consumer data simply passes to a new owner.

My Data Union addresses these systemic abuses by implementing a transparent framework for lawful, consent-based data exchange. By granting members precise control over what information is shared and under what conditions, it eliminates the incentives that drive unauthorized extraction and resale of personal data.

[4.0] Why consumers should organize with My Data Union

Consumers know there is a problem but lack a viable path to fix it. According to a December 2024 Deloitte survey, about 80% of consumers believe they have inadequate control over the data collected about them and that companies fail to communicate clear privacy expectations.[28] Individually, consumers are powerless to shift the balance and must shoulder the costs themselves. Companies that collect consumer data need to face sustained, organized resistance to deliver fair treatment. It is naive to expect market participants will voluntarily reform a system that services their financial interests, or to solely rely on government intervention for equitable, lasting change. They need help from an aligned organization. My Data Union offers its members the following:

- A platform to safely collect, anonymize, and monetize their data;

- Collective negotiation and oversight;

- Market activism to defend its members’ best interests.

[4.1] To safely collect, price, and sell their data

The scales of the digital economy need an adjustment. One side of the market operates with the sophistication of high-frequency trading systems while consumers remain effectively analog in a digital economy. The solution is simple: consumers need fair financial incentives and the right tools to compete.

The first step is to for consumers understand what is already being taken from them, and what it is worth. Members can achieve this by installing My Data Union’s tools on their devices to autonomously collect information solely for the members’ benefit. In practice, this means all collected information resides locally on the member’s device, encrypted and inaccessible to anyone else, until the member explicitly chooses to delete or share it. It can be used to identify all the information they leak to others and why others pay for it. From there, My Data Union offers members safe methods to share what they want and sell to qualified buyers for the best price.

[4.2] To dictate the fair use of their data

As discussed earlier, the exchange of consumer data is governed poorly. The system incentivizes invasive data sharing practices, cross-border transmission of sensitive information, and the concealment of unethical activity. None of the companies involved are motivated to fix the problem; however, many recognize it. They need a competitive option. Organized consumers can fill the gap themselves and source vast quantities of consensual consumer data under the right conditions. My Data Union’s platform helps them do it.

No participant in the data economy is more affected by consent and access lapses than the consumer. As rightful owners of their digital property, consumers are natural gatekeepers of how it is gathered and used. Members of My Data Union retain full control over the data they collect. They can review data stored locally on their devices as well as the information they share with My Data Union. If, at any point for any reason, a member decides they no longer want to share a subset of their data, they can delete it from their logs and cut off access.

[4.3] To negotiate for and monitor terms

Predatory practices thrive when monitoring and enforcement are weak. Even major mobile app store operators, who are central to the data ecosystem, are not immune to governance failures. Numerous scandals and lawsuits revealed conflicts of interest that discourage strict enforcement of consumer protections.

The misalignment is structural:

- App store operators earn around 30% of all app-generated revenue. The more successful a developer becomes, the greater its leverage over the platform.

- Reviewing and enforcing terms of service requires significant time, cost, and expertise.

- Over time, top developers use their leverage to push new, one-sided terms that disadvantage users but increase revenue.

- App store operators and developers share a common incentive, which is to maximize profits and minimize compliance costs.

As a result, app store operators are not properly incentivized to reject overreach. It is critical for consumers to be inserted during this process. People need representation they can trust to lobby for them while terms are being drafted. My Data Union helps people restore the principle of informed, balanced participation in the digital marketplace.

Bad actors, intentional and accidental alike, need to be identified quickly so they can either reform or be removed. Persistence is the key to detecting and defeating their behavior. My Data Union can provide members with an informed opinion about emerging threats and publish its own investigations to shine a light on malicious practices.

[4.4] My Data Union’s vision

My Data Union works for a future where its members are part of a represented, knowledgeable group of empowered owners who manage their data with conviction. They are recognized as informed participants who require fair and transparent terms for a consensual exchange. They stand ready to defend their autonomy and protect themselves from exploitative middlemen.

The creation of My Data Union was modeled after one of the largest American labor unions, the United Auto Workers (UAW). Within its constitution, it contains many inspiring passages about the why the union formed and for what purposes. One of the passages describes people who are robbed “of their dignity as an adult human being” when they are treated as an “adjunct to the tool rather than its master.[29] A similar trend is afoot; people are considered “the product” by the services they use. My Data Union’s purpose is to change that perception to “the owners.”

My Data Union made bold choices to promote internal representation for its members. It was established as a Public Benefit Corporation. This designation allowed the company to legally recognize its members as the rightful owners of their digital property in its incorporation documents. To ensure the principles are practiced, My Data Union’s board of directors includes a permanent seat for a member-elected representative. The structure goes way beyond what other companies offer to consumers. My Data Union is committed to create long-term value for members and shareholders through transparency and trust.

[1] https://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy-research/tech-at-ftc/2024/12/unpacking-real-time-bidding-through-ftcs-case-mobilewalla

[2] https://www.insideprivacy.com/health-privacy/flo-health-google-settle-class-action-privacy-lawsuit-for-56-million

[3] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2019/12/ftc-issues-opinion-order-against-cambridge-analytica-deceiving-consumers-about-collection-facebook

[4] https://www.ftc.gov/node/44679

[5] https://www.mastercardservices.com/en/capabilities/spendingpulse/spendingpulse-platform

[6] https://www.zendesk.com/blog/4-customer-engagement-metrics-measure/#

[7] https://aws.amazon.com/solutions/case-studies/the-coca-cola-company-case-study

[8] https://guides.lib.unc.edu/market-research-tutorial/demographics

[9] https://plaid.com/resources/lending/alternative-credit-data

[10] https://drj.com/industry_news/new-incogni-study-reveals-massive-data-sharing-and-privacy-risks-in-popular-buy-now-pay-later-apps

[11] https://www.mx.com/use-cases/financial-wellness

[12] https://epic.org/documents/epic-cfpb-complaint-rocket-money

[13] https://www.vice.com/en/article/location-data-firm-heat-maps-planned-parenthood-abortion-clinics-placer-ai

[14] https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/insights/data/alternative-data-insights-consumer-spending-growth-in-2025

[15] https://crawlbase.com/blog/how-hedge-funds-use-web-scraping

[16] https://www.interactivebrokers.com/campus/traders-insight/securities/macro/chart-advisor-exploring-sentiment-analysis-with-stocktwitsre

[17] https://www.reuters.com/world/reddit-sues-perplexity-scraping-data-train-ai-system-2025-10-22

[18] https://searchengineland.com/openai-may-pay-reddit-70m-for-licensing-deal-451882

[19] https://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy-research/tech-at-ftc/2024/12/unpacking-real-time-bidding-through-ftcs-case-mobilewalla

[20] https://www.warren.senate.gov/oversight/letters/warren-leads-senators-blasting-data-brokers-for-collecting-and-selling-cell-phone-location-data-of-people-who-visit-abortion-clinics

[21] https://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy-research/tech-at-ftc/2024/03/ftc-cracks-down-mass-data-collectors-closer-look-avast-x-mode-inmarket

[22]https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2022.05.17%20Letters%20to%20Safegraph%20and%20Placer.ai% 20re%20Abortion%20Clinic%20Data.pdf

[23] https://www.wired.com/story/gravy-location-data-app-leak-rtb

[24] https://www.mcafee.com/blogs/security-news/data-breach-exposes-3-billion-personal-information-records

[25] https://www.pointr.tech/blog/wifi-or-beacons-for-indoor-location

[26] https://www.pointr.tech/blog/wifi-or-beacons-for-indoor-location

[27] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/01/ftc-order-prohibits-data-broker-x-mode-social-outlogic-selling-sensitive-location-data

[28] https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/about/press-room/increasing-consumer-privacy-and-security-concerns-in-the-generative-ai-era.html

[29] https://uaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Updated-2022-Constitution-8.30.23.pdf